The calls to address employee wellbeing are becoming more frequent and louder within organisations and at various forums (whether in the news or the many webinars and peer-sharing platforms). This is related in part to the difficult decisions that organisations are making on how they deploy, manage, and engage their workforce, especially with the acceleration of flexible and remote work in some segments of their workforce. Separately, there are also calls for the need to address productivity. This has rekindled the heated debates and questions on what productivity is, and how do we measure and manage it. At first sight these two calls, on wellbeing and productivity, seem separate or the distinct mandates of different functions within an organisation. However, the reality is that organisations need to address both wellbeing and productivity together, especially in the now always-on digital workspace.

It certainly is a paradox that organisations need to engage with and manage holistically. The large-scale experiment in flexible and remote work during this COVID pandemic is reinforcing this need. It illustrates how we need to consider the wellbeing of the workforce in the design and management of work and the workplace. Wellbeing is not an adjunct, supplementary, or ‘after the fact’ consideration to the ‘hardwiring’ of the organisation and the questions on productivity, outcomes, and value creation of the organisation. In fact, the integrative reporting framework identifies human capital as one of the five capitals that firms need to report on, in terms of the impact of their activities on these through their value chain. This means that organisations need to manage the link between wellbeing and organisational outcomes throughout the value chain. This is also the message within the Deloitte’s 2020 Human Capital Trends report, “The social enterprise at work: Paradox as a path forward”.

The first step to engaging with and managing the paradox of wellbeing and productivity is to identify and prioritise the core themes that are relevant to your organisation. This article helps by drawing out some of the emerging common themes. It focuses on themes in relation to remote working and the digital workspace, which can also apply in some respects to the physical workspace. The themes are discussed below.

Uptime/online and downtime/offline

The COVID pandemic and worldwide lockdowns were the trigger for organisations to go remote and digital where possible. In this sudden remote and digital immersion, organisations carried with them two contrary expectations. There was the expectation that the organisation could function, as is, in a remote and digital way. The assumption was that of a plug-and-play solution, where remote and digital work could simply plug into the organisation’s legacy processes, systems and practices, and allow work to continue as is. However, there was also the expectation that digital technologies would cause vastly increased levels of individual, team and organisational productivity. We found, though, that the realities of the remote and digitally enabled work and workforce are not that clear cut and simple. It is not simply plug-and-play, nor do technologies by themselves cause profound shifts in productivity. It requires deliberate thought and action, that is, organisations need to explicitly define productivity, the shifts required and how these will be achieved and managed.

Organisations are now realising that there needs to be a broader organisational transformation strategy and programme. Being online and productive is rather complex and requires systematic wellbeing, learning and development, engagement, and performance management interventions for example. There is the need to balance being online and offline that allows for employees’ productive engagement, flow, and downtime. The dangers of being constantly online can be seen in the digital and psychological fatigue that many now talk about – whether it is “zoom-fatigue”, “Teams-fatigue”, or “webinar-fatigue”. The extended hours of work, being constantly available, and the squeezing in of webinars is physically, mentally, and emotionally draining. Some whisper about the possibility of burnout, especially with the anxiety of being constantly monitored in the digital world. In the recent research by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) on workplace technology, for example, they found that “around a quarter of employees say their work has had a negative impact on either their physical (24%) or mental health (26%)” (2020).

What is forgotten with the organisational demand that employees be available and online for extended hours, while also absorbing learnings in between, is the importance and role of our resting downtime states. It is in these states that we actually process, consolidate our memories and learning as well as reflect and plan. We are reflecting on our selves, others, and our pasts and futures – here the default mode network of the brain is active. This is when we recharge and re-energise.

Boundary, role, and identity management

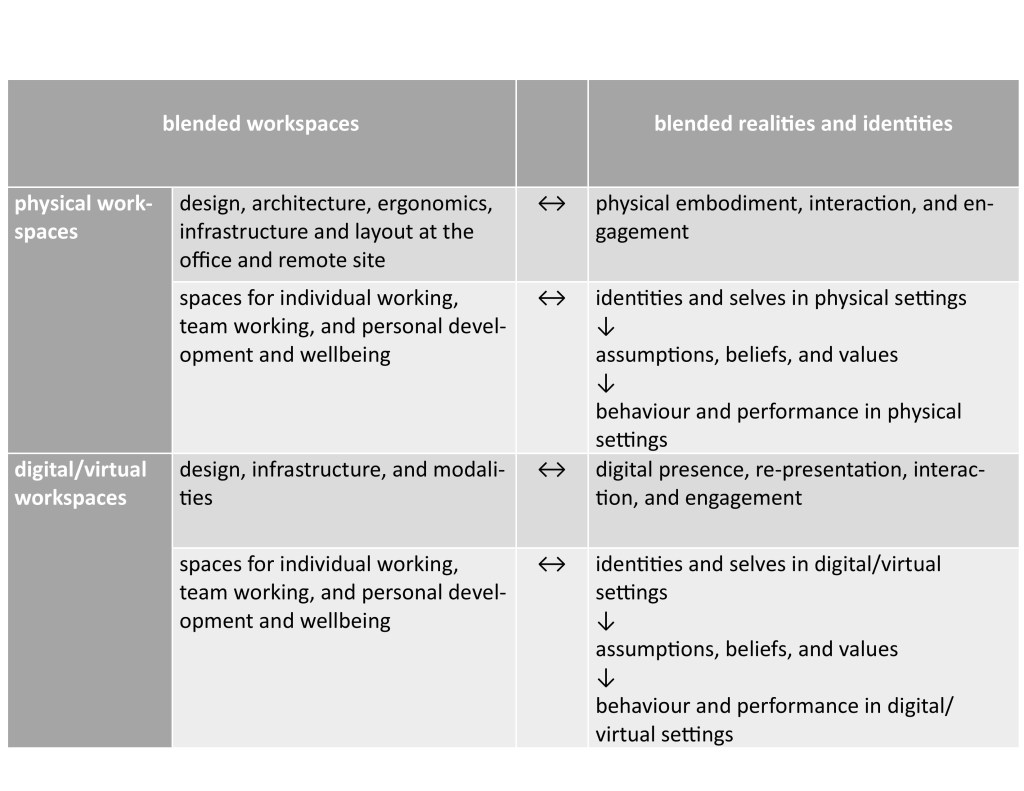

Working from home has blurred the lines between our work and personal lives. With remote working and mobile and other technologies, it not just the blurring of lines, but the collapse our work and personal spaces and boundaries. Within the confines of our home we are now fulfilling different and competing roles that we previously used to in different spaces. The considerable research on the bi-directional role and gendered conflict between work and family, namely, work-to-family-conflict and family-to-work-conflict, can help to understand these dynamics. There is also research on work and family enrichment, where the roles could enrich and enhance each other. The pandemic, lockdown, and new normal of work presents us an opportunity to take stock of our lives and the various roles and identities we perform, but could also easily lead to fear, loathing, and disarray that negatively impacts wellbeing and productivity.

Employee surveillance and voice

With the blurred boundaries, spaces, and times employees fear being constantly monitored and measured at a very granular level. The CIPD’s (2020) research found that:

- “45% of employees believe that monitoring is currently taking place in their workplace”

- “86% believe that workplace monitoring and surveillance will increase in the future”

Employees are aware that monitoring software makes visible each and every minutiae activity, ‘non-activity’, and error or slip-up – from their clicks and browser history, their time spent on applications to detailed analytics on their online times, communication patterns, meetings, collaboration, focused time, and task completion. For managers, the monitoring software can be rather ‘seductive’ in that it gives a false sense of being in control and measuring (rather than managing) employees. However, they themselves fear being visible and monitored 24/7, which means defensive and risk-aversive decisions and behaviour as they themselves are triggered by the surveillance as are their employees.

This sense and reality of constant monitoring and surveillance can negatively impact on trust, engagement, and ultimately the achievement of organisational outcomes. For example, in the CIPD research, “73% of employees feel that introducing workplace monitoring would damage trust between workers and their employers”. The constant monitoring and surveillance will also impact on employees’ wellbeing, as they will feel constantly triggered and in danger. This will exacerbate the negative impact on individual productivity and the achievement of organisational outcomes, especially if there is no consultation. Employees will feel as if they do not have a voice and may feel disempowered and become more disengaged as they feel their job quality will be impacted. This can be seen in the CIPD research:

- “Only 35% of employees and/or their representatives have been consulted on the introduction and/or implementation of new technology”

- “Where employees have not been consulted about technology change, only 20% are positive about the likely impact on their job quality, compared with 70% for those who have been consulted”

It boils down to the old choice, are organisations wanting to measure time and presence (in this instance, online-times and clicks-and-keyboard-strokes) or outputs and outcomes.

Psychological safety, productive space and mindset, and performance

The above issues of trust, fears and triggers does impact on employees’ sense of psychological safety, a construct developed by Amy Edmondson (1999). The construct reminds us that it is not just individual triggers, but also interpersonal and structural factors as well that are important and that ultimately impact on team learning and performance. The serious attention that is again been given to psychological safety, then, is not only focused on individual adjustment and coping during the COVID pandemic, but also the dire socio-economic effects of the pandemic that are unfolding and employees’ feedback on both the positive and negative impacts of being online for extended periods and of their protracted uptime.

With the extended uptime and the pervasive and constant monitoring and surveillance, there is also the possibility of dislocation and disconnection from working remotely and virtually. We may feel dislocated because we are intellectually in one space, emotionally in another, and physically in a different space. This is compounded by the convergence of personal memories and memorabilia, office equipment, and the virtual presence of team members and managers on our screens. We feel as if our minds, emotions, and bodies are in different spaces and at different tempos.

“[..] we are fooled into believing we have more and stronger social connections in the online world, but they don’t trigger all the positive biological responses that real social engagement brings” (Mortensen, 2020)

With dislocation there is also the possibility of disconnection. Although we may be present to our team members and they present to us, digitally, this is not the embodied engagement and social connections of face-to-face interactions. This may engender feelings of isolation, thoughts of being left out, and not being able to identify with the team and organisation. Thus, we may lose the sense of belonging. That is, belonging to a place and to a purpose. This is the organisation as represented physically and spatially and its vision, mission, and purpose.

It is not just belonging that needs to be addressed. Organisations can help employees create productive spaces and mindsets to regain perspective, focus and productivity. They need to demarcate space and times for employees to recompose and recharge themselves and reflect. As mentioned earlier, we need to take stock of where we are at mentally and emotionally.

Through the discussion of the above themes one notes how wellbeing, productivity, engagement, trust, and achievement of outcomes are interwoven, especially in the digital workplace. These need to be addressed deliberately and together in a coherent organisational transformation strategy and programme. Digital technologies by themselves are not the ‘magical elixir for the ills’ of organisations as they navigate the pandemic and the new normal. Flexible and remote working and the broader digital transformation requires hard work on and within organisations, by organisations themselves. Organisations need to navigate and manage the paradox of wellbeing and productivity together with the other paradoxes that confront them.